I’m just now beginning to edit together on iMovie some of the footage I took with our digital recorder last summer in Hilton (Yes, but does it have enough arch support?) Head. When my Mom turned 60 back in January of 2005 she had already made it known that what she wanted most was for all her children and their families to stay under one roof for a week on Hilton Head. My parents had owned a place there for over a decade, a cozy two floor condo with a late 70’s vibe and conveniently located across the street from the beach, before recently selling it and buying another, with a better view of the Atlantic, in the warmer climates of Tarpon Springs, Florida. Over those 10 years their condo in Hilton Head had served as the hub of numerous Breitenbach vacations, though the last time we had all been together, the last time we had all spent a week heading out to the beach or pool together for lazy afternoons and out to dinners in humidity swamped evenings was in the summer of 2002 when we all came together to celebrate my Dad’s own 60th.

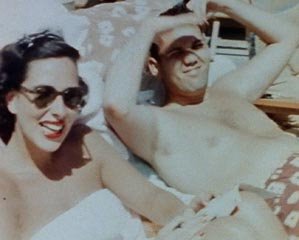

I’m just now beginning to edit together on iMovie some of the footage I took with our digital recorder last summer in Hilton (Yes, but does it have enough arch support?) Head. When my Mom turned 60 back in January of 2005 she had already made it known that what she wanted most was for all her children and their families to stay under one roof for a week on Hilton Head. My parents had owned a place there for over a decade, a cozy two floor condo with a late 70’s vibe and conveniently located across the street from the beach, before recently selling it and buying another, with a better view of the Atlantic, in the warmer climates of Tarpon Springs, Florida. Over those 10 years their condo in Hilton Head had served as the hub of numerous Breitenbach vacations, though the last time we had all been together, the last time we had all spent a week heading out to the beach or pool together for lazy afternoons and out to dinners in humidity swamped evenings was in the summer of 2002 when we all came together to celebrate my Dad’s own 60th. So I filmed about 50 minutes of footage last summer- Cathy and I packing, my nieces and nephews playing in the pool, all of us singing Happy Birthday, a sunrise, sand castle building on the beach. I’m not too good at premeditating what I’m going to shoot or why, though I’d like to be. I’m still learning how to keep the camera near and how to reflexively take it up and begin filming. I’m learning about how cameras can steal the spirit of some and bring out the rascal in others. I’ve got a lot to learn. But mostly I’m still enthralled by how what ultimately is filmed, edited or not, can accumulate a kind of mythic resonance within families and become part of family folklore.

So, given that I’m prone to thinking about such things, I was especially excited to see that Joe had a link on his blog a couple months ago to Folkstreams.net, a site whose mission includes building a “national preserve of hard-to-find documentary films about American folk or roots cultures” and “to give them renewed life by streaming them on the internet.” And not just that! When browsing through their catalog of subjects, under the heading "Arts and Crafts Traditional" I found a link to the 19 minute documentary “Home Movie: An American Folk Art,” made in 1975 for a Smithsonian Institute festival. The filmmakers (Ernst Edward Star and Steven Zeitlin, then graduate students) had put out a call to the public to send them their home movies and photographs with the goal of then studying and editing them into Home Movie. According to the documentaries accompanying blurb, after sifting through all these family movies and photographs, Star and Zeitlin “began to see that, just as certain categories of stories recur from family to family, certain kinds of images recur in home movie archives. Scenes of holiday celebrations, birthdays, picnics, and vacations dominate these collections, and children, from infancy through high school graduation, at the mercy of their parents, are favorite subjects for the home photographer.”

The documentary itself is priceless. Not simply because the filmmakers interests helped to give my own inchoate fascinations with this subject some glimmers of coherence but because the documentary itself, now over 30 years old, has taken on and accumulated its own patina of funky nostalgia. Watching the documentaries first few minutes, where one of the filmmakers (Zeitlin, I’m guessing) appears sitting next to a projector dressed in what now radiates a kind of grad student geek chic and soulfully, earnestly pontificates (he seems to be reading directly from his thesis) about what lies at the heart of our need to record these moments, these holidays, birthdays and vacations, I was struck by how much it resembled a scene or an outtake from a Wes Anderson film. I thought, if Wes Anderson is one of the current masters of mining a very specific kind of Americana quirky, then this introduction was one of his templates. I also really liked what Zeitlin was saying. Speaking about what makes home movies a “unique folk art” he expounds that,

…where the art comes into it is in the act of selection. Why, for instance, did my parents film that particular scene? I figured out that I must have spent close to 150,000 hours at home before I went to college. How many of them could have been spent playing in the pool?

Clearly homes movies are not a random sample of our past but an idealization based on how we chose to preserve, remember and be remembered. From one perspective, home movies reflect the ideals of a particular family. For my parents, it was their home, their kids, their puppies, their little yellow pool with the 4 horses on it. It was what was distinctive and what was memorable about their own family that they sought to preserve on that sunny afternoon. I watched hundreds of home movies and saw hundreds of water sprinklers and planted pools. I began to realize that on another level, homes movies are an American tradition and as such they tell us something about American values and ideas. In that simple scene of youthful parents, happy children and a backyard swimming pool we catch a glimpse of an American dream.

What follows is a montage of scenes demonstrating this American dream—of children mostly-- children running through snow, jumping in leaves, playing on beaches, taking baths, newborns wrapped in swaddling, having birthday parties, enjoying Christmas morning, dancing-- all accompanied by a delicately mournful Eric Satie piece for piano. Theres a strong whiff of melancholy to it, these seemingly random moments that have been conferred a special kind of meaning simply because they were privileged with having been filmed. Soon our graduate friend Zeitlin returns to get all elysian and informs us that home movies are endowed with, in fact, a third and “universal level” of values depicted in home movies, the first two being the values “important to individual families” and “America as a whole. “ But what are these so-called universal values? Thankfully, Zeitlin throws it down for us:

By attempting to preserve that which is most beautiful to his life, the home movie maker might be seen as partaking in what seems to be a universal desire to create a golden age. From Shangri-La to Eden man has always needed visions of peace and harmony to guide him through the inevitable complexities of his present world. The home movie maker may be no more aware of the fact that he is filming a golden age then Adam and Eve were that they were living in paradise. But to an individual family, the world depicted in home movies might serve as their own golden age.

For the remainder of the documentary, Zeitlin and Star visit members of three of the families who had responded to their open call for footage and have them provide commentary as they watch their home movies together, a precursor to the director/actor commentary now found on so many DVDs. The filmmakers don’t ask too many questions that would support their thesis of home movies being conduits for a lost golden age, choosing instead to let the families randomly enthuse about how somebody always sits in the sun in just such a way, and how this or that uncle still has the same hairstyle 20 years later and how it hardly seems like a decade has passed since that wedding. birthday or graduation.

Now that simple editing software comes bundled with home computers, I’m interested in how many people are using these tools to construct narratives out of the more or less random footage they’ve taken. How do you create an additional layer of meaning or thematic structure to this footage and make it something more then a collection of disparate shots? How do you arrange it in such a way, edit it, so that it tells an engaging story? It's time for some new folklorists to step up and make a documentary about how children of the digital age and their parents have and will continue to create folk art by what they select to film and, more importantly, what and how they chose to edit.

My friend Julie told me yesterday afternoon that her daughters love to watch footage of themselves taken over the years. “It’s like a Disney movie for them,” she said, “you just put it on and their happy as can be.” And I find myself wondering how these movies and their repetitive viewings of them help (or hidner?) to shape memories and identities. How will they come to know themselves, their childhood, through these videos? How does video, as film critic Jonathan Romney once wrote, become a “prosthesis for human memory?” How rich and strange to think of the multitude of raw footage taken of their lives they’ll have to look back on when I compare it to my own archive of footage-- a fleeting 2 or so hours of super-8 my Dad filmed from roughly the late 60’s to the late 70’s. Footage, I might add, that languished for almost 20 years in various closets and attic crawl spaces before my Mom had them converted to DVD.

Ross McElwee, whose work I love, is probably the foremost purveyor of this personalized cinema verite I find myself so interested in. He’s certainly one of its most eloquent elucidators. A few years back when Cineaste interviewed him he had this to say:

McElwee: I think it’s going to be very interesting, by the way, to see what happens with this digital generation of parents who have recorded their kids’ every footstep. People were shooting a fair amount of super-8 film in the Sixties and Seventies. But it was expensive and difficult to load, and editing it was extremely time-consuming. Most people didn’t edit their footage; most footage was not viewed more than once. Digital video, or video in general enables parents to keep a constant record of a family as it grows up. So that very question you raised- “Am I remembering this correctly?”- needn’t be an issue. People can just go back to the data bank and see exactly how little Jimmy spooned his peas into his mouth at age four. There’ll be a record of it. And how strange is that?

How strange is that?

No comments:

Post a Comment